Since ancient times, humans have used animals as “meteorological indicators.” The most famous example of this is the proverbial “weather frog.” And for good reason, as some frog species actually exhibit noticeable changes in behavior in response to changing weather.

But to be precise, it’s not primarily the frogs that directly react to the weather. Instead, they follow their preferred food—flies and mosquitoes—to where these insects are more abundant depending on the weather: flying higher up in good weather and staying closer to the ground in bad weather. Accordingly, the frogs, with their long tongues, tend to stay closer to the ground or climb higher in the vegetation. (By the way, swallows do the same: they also adjust their flight altitude based on where their prey is.)

However, this doesn’t work as well for frogs kept in a glass with a ladder—fortunately, we are long past the times when animals were kept in such cruel conditions. Today, we have much better options for housing our amphibians and reptiles in habitat-like, natural environments—while also providing optimal living conditions for them through individually tailored climate control.

The (climbing) frogs, by the way, are not the only “meteorologists” in the amphibian or reptile kingdom. For example, fire salamanders in the wild are only active during rainy weather. If it’s sunny, their sensitive skin would dry out too quickly. In contrast, lizards are the complete opposite: they are true sun worshippers, which is why you’ll only see them in the wild on “nice weather” days.

While these observations are quite clear, they are less useful for weather forecasting. That’s because, when you observe the typical weather-related behavior of these animals, the weather they’re responding to is already “there.”

The best forecaster: The spider.

Spiders are more interesting as true weather prophets. For example, weather.com crowns cross spiders as the “weather animal number 1”:

When web spiders are actively building their webs, it means the weather will be calm and dry. […] On the other hand, rain or even thunderstorms are likely if spiders retreat into their hiding spots and don’t come out, even while the weather is still good.

https://weather.com/de-DE/wissen/klima/news/wetterpropheten-flora-fauna-wettervorhersage

Weather sensitivity underwater

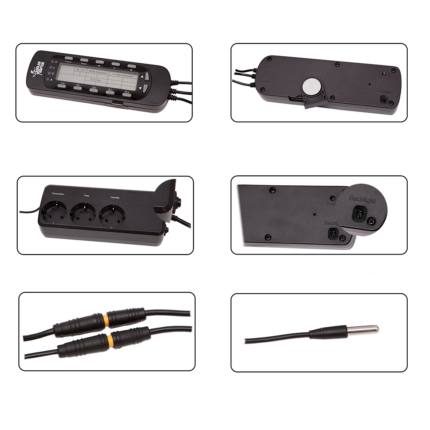

SOLAR RAPTOR® Timer Controller

- Switchable socket strip

- CON-T: Temperature/time control

- CON-TH: Temperature/humidity/time control

- Quick setting desert/tropical mode

incl. VAT

plus shipping

Reactions to certain weather are widespread in the terrestrial animal kingdom. But what about underwater? Can fish and other aquatic animals even perceive weather changes? It has long been known to fishermen that fish react to rain: “Fish bite better when it rains” is an ancient saying.

The sound of pouring rain is, of course, perceivable underwater as well. And since the water surface becomes murky due to the disturbance caused by raindrops, it’s also logical that fish feel safer in the upper water layers during such times. This way, flying predators have a harder time spotting and catching them.

But what about in an aquarium? After all, even during the strongest thunderstorms, no rain is actually falling on the water here.

Still, most aquarium owners would likely answer the question of whether their animals react to certain weather conditions with a yes. After all, every aquarist who observes their animals has probably noticed that their fish eat differently depending on the weather, may retreat, or that a specific weather pattern even acts as a trigger for reproduction.

Spawning during thunderstorms.

An example of the latter are the armored catfish (Corydoras) from South America. While there are many factors at play in their natural spawning behavior, such as the overall interplay between the rainy and dry seasons, a specific weather pattern often proves helpful for triggering spawning in aquariums—namely, rain or thunderstorms.

The explanation for this is likely based on an increased survival rate for the offspring in nature during rainy weather conditions:

When a low-pressure system approaches, the air pressure changes, and wind often accompanies it. Insects fly lower and are pushed onto the water by the wind. When rain arrives, small creatures and plant matter are washed into the water, improving the food supply. Sediment runoff in the shore regions causes murkiness, offering better cover from predators. Additionally, in watercourses that experience strong volume fluctuations, rain means that at least the subsequent period will likely not threaten a spawning site with drying out, thus providing an expanded habitat overall.

All these advantages have ensured that the catfish, which can “sense” low-pressure systems and respond with their reproductive behavior, have an evolutionary advantage through a higher success rate in reproduction. As a result, this “weather sensitivity” has been genetically established.

Tricks help with breeding

Knowing this helps aquarists with breeding. With this knowledge, they can apply various “tricks” to trigger spawning. For example, by adjusting the feeding regimen in combination with artificially induced temperature fluctuations (e.g., through water changes), they can try to simulate a “reproduction-friendly climate” in the aquarium.

And if that doesn’t work? Then there’s always the option of hoping for the approach of a thunderstorm front…

Profile image: Rainbow over the island of Giglio. Photo: Federico Burgalassi via Unsplash.