Many myths and stories surround the giant clams of the genus Tridacnidae. They are often called ‘killer clams’ and ‘killer mussels’ – quite wrongly! However, the myths that have been created show one thing above all: these animals have always been a source of fascination. The fact that the Tridacna can also be kept in seawater aquariums, however, is still

largely unknown. Yet these fantastically beautiful mussels know how to excite here too!

This article is part of a series of articles on “Experiences with saltwater aquariums”. In this loose collection, our author Andreas Berns — an aquarium consultant with many years of experience with aquariums of all types and sizes — reports anecdotally and entertainingly on special aquarium inhabitants, interesting integration projects and curious experiences. He also gives valuable tips on keeping the species described.

The following stories have been published so far:

Beware of poison: Lionfish in the reef aquarium

Pretty clever: a pallet doctor moves house & gets socialized

Tridacnidae: A myth in the sea

Tough little gemstone in the marine aquarium: the horse actinia Actinia equina

The ‘wrong picture’

‘Killer clam’ – unfortunately, this is still often written on the sales tanks in pet shops, in book descriptions and even on the display aquariums of some zoological gardens. This is actually irritating because dealers, authors and zoo staff know better, of course. But they still use the myths and rumours surrounding the giant clams for better marketing.

Stories continue to circulate of alleged diving accidents in which giant clams are said to have grabbed people with their mighty shells and held them down. However, not a single authentic case is known in which a person was ‘caught’ or killed by a giant clam.

The only danger the mussels pose to humans and animals is that of accidentally reaching between the shells and thus triggering the mussels’ closing reflex.

The belief in the stories about the supposedly dangerous giant clams is not supported by real experiences, but rather by ignorance of the history of the origin and way of life of these beautiful animals.

The giant clams of the Tridacnidae family have already attracted a great deal of attention in the past and outside of animal research or aquaristic topics:

Since the Middle Ages, giant clam shells taken from nature have been used in churches as holy water and baptismal fonts. In the Indo-Pacific region, the thick shells of the animals were and are used to make tools and figures for ceremonies. On the Solomon Islands, the shells were cut and used as a form of currency, symbolising the wealth of a tribe. Due to their size, the pearls of tridacnidae shells were often the subject of material and ritual reenactments – one of the largest known pearls reached a weight of seven kilograms and a diameter of 23 centimetres and became world-famous under the name ‘Allah’s Pearl’.

All these circumstances – coupled with the often gigantic growth and the almost unreal beauty of their appearance – fuelled the false image of giant clams for a long time.

Descent and origin

The family Tridacnidae belongs to the order Eulamellibranchia and as such to the class Bivalvia (bivalve molluscs). All bivalves belong to the phylum Mollusca (molluscs), as do snails, squid and some other classes.

Based on fossil finds, the evolutionary history of giant clams can be summarised as follows:

Vor über 600 Millionen Jahren (im Präkambrium) entwickelten sich aus einem primitiven „Urweichtier“ die ersten Mollusken. Damals wie heute war fast allen Mollusken ein schalenförmiger Körperschutz gemein, wie z.B. bei den späteren Schnecken und Muscheln. Nur in der evolutionsgeschichtlich sehr jungen Familie der Cephalopoden (Kopffüßer) haben viele Arten (Tintenfische) die ehemals äußere Schutzschale zu einer im Körperinneren sitzenden kalkhaltigen Substanz (Schulp) oder in hornige Form (Schnabel des Tintenfisches) umgewandelt.

The oldest fossil finds of the first shells (Bivalvia) date back to around 400 million years ago (in the Silurian). The actual development is thought to date back to the Cambrian or Ordovician period (425 – 500 million years ago). The Bivalvia succeeded in solving the problem of almost complete body protection by splitting their original protective shell into two halves, which are connected by a holding and closing hinge. The development of giant clams is also thought to have taken place during this epoch.

Giant clams – a very special species

The Tridacnidae family inhabits the Indo-Pacific region. The best known is Tridacna gigas, whose shell is over 130 cm long and can weigh up to 250 kilograms. While the other mussel species almost all prefer to hide upside down (i.e. with the shell hinge facing upwards) and often bury themselves in the substrate, the giant clam always remains exposed. Unlike ‘normal’ clams, which stand upright in the sand with the shell hinge facing downwards and the lock facing upwards, the Tridacna lies between the corals with its stomach facing upwards. The shell lock is pointing downwards and the mantle edge is clearly extended upwards.

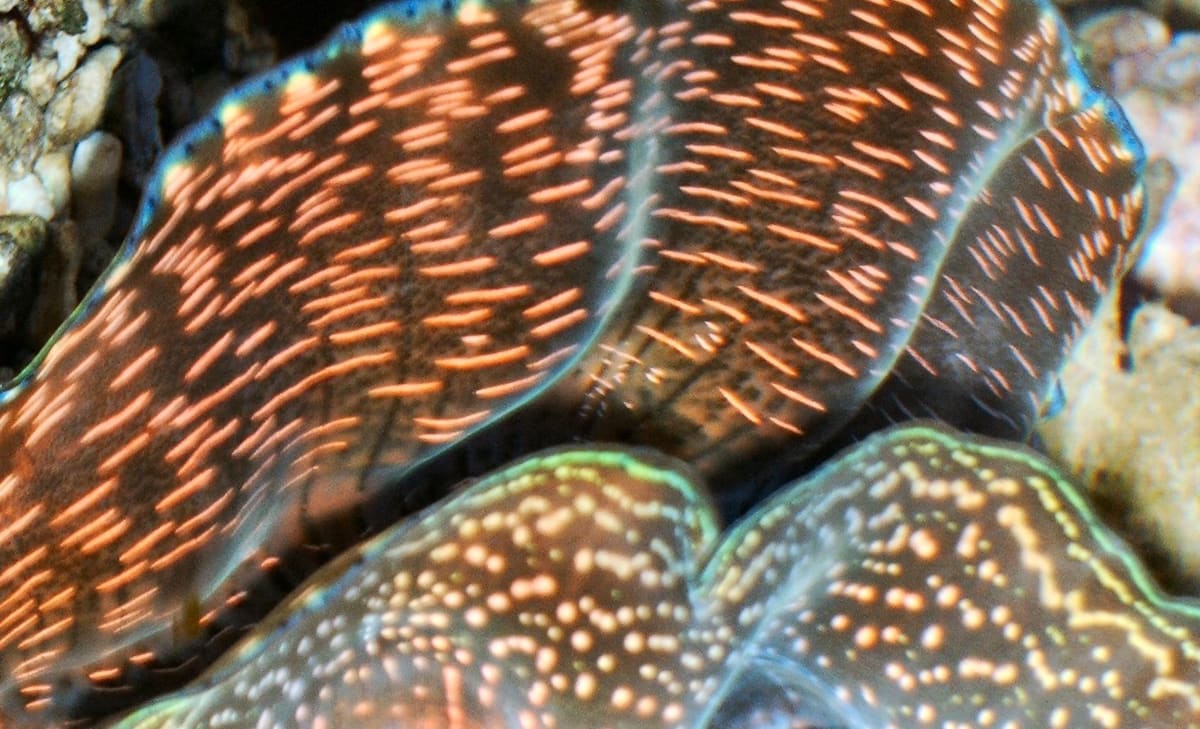

The brightly coloured mantle can be seen through the open shell halves, with colours ranging from orange and purple to blue and green. The mantle is often decorated with brown, black or shimmering metallic stripes and spots. Whenever light hits the mussel, it holds its brightly coloured mantle up to the sunlight.

Questions and answers

The first marine biologists to study giant clams in their habitat were initially faced with many unresolved questions:

All known mussel species live on what they filter out of the water – but how can such a large animal survive in the extremely nutrient-poor waters of coral reefs? How does it satisfy its great need for food? And where does the enormous luminosity of the mantle come from and what is its purpose? And finally: How do giant clams reproduce?

Surprising answers

Research into the animals has led to some surprising answers to these questions. The most important: the giant mollusc survives in the nutrient-poor reef waters with the help of a symbiosis that it forms with zooxanthellae (unicellular algae).

The giant clams begin to cultivate algae (zooxanthellae) in their mantle seam as early as the larval stage. From as early as the third week of life, the larvae remodel their bodies according to the needs of the algae to be cultivated. The shell hinge, which is initially at the top as in all other mussels, moves downwards, the breathing tubes move upwards and become many times larger than the mantle lobe.

The development of a special canal system that runs through the entire mantle lobe creates a settlement area for large quantities of zooxanthellae.

The mussels therefore create the best possible conditions for the algae that are so important for their survival. While the young mussel larvae still feed mainly on the finest plankton and dissolved food substances that they filter out of the water, the fully developed mussels feed almost exclusively on the photosynthesis products of the algae.

To do this, the mussels stretch their mantle with the zooxanthellae inside towards the sunlight. Only in this way can ‘their’ algae carry out photosynthesis and they themselves feed on their photosynthesis products.

In return, the algae receive (in addition to the ‘settlement area’ itself) metabolic products from the giant clams as well as protection and perfect light conditions.

Built-in lenses improve the light output

The need to ‘supply’ the algae with perfect light conditions also answers the question as to the reasons for the enormous luminosity of the mantle: this is based on iridocytes, tiny lenses made of organic material, which the mussel uses to set the right light level for the algae’s optimal photosynthesis process. A side effect is that these lenses reflect part of the captured light outwards and thus create the luminosity of the mantle.

The growth of the giant clams is directly dependent on the functioning nutrition provided by the zooxanthellae. Depending on the quality of the supply of light and nutrients to the symbiotic algae, the size growth of the mussels themselves varies greatly. Phases of growth are followed by phases of pause. Climatic and nutritional bottlenecks are reflected in slower or even stagnant shell growth, which is reflected in narrower or irregular growth lines on the shell.

And finally, the question of how giant clams reproduce was also quickly clarified by observations in nature; it is analogous to the processes of other sessile marine animal species:

Controlled by the lunar cycle, but also stimulated by deteriorating water parameters, the Tridacnidae eject either eggs or spermatozoa into the water. Fertilisation takes place in open water, where eggs and spermatozoa of the same species meet. Conservation of the species is ensured by the very large number of eggs and spermatozoa ejected: hundreds of millions each time for an adult animal.

Commercial mussel farms have capitalised on these observations and now produce large quantities of offspring. A large proportion of them end up in the sales aquariums of pet shops, while an even larger proportion – particularly in Asia – are eaten.

Giant clams in an aquarium

Almost all smaller species of Tridacnidae can be kept well and for a long time, especially in the reef aquarium. The prerequisite is the purchase of healthy, not too small animals. You should examine the animals thoroughly before buying them:

- The shells must not show any damage (especially cracks) from transport. Tridacnidae are very difficult to regenerate such damage under aquarium conditions.

- The animal should have been in the dealer aquarium for at least 2 weeks. Moving it again during the first 2 weeks means life-threatening stress for many animals.

- The sheathing flap must be undamaged!

- The animal must not show any bleaching on the mantle lobe.

- The byssus apparatus (glands for producing the byssus threads for anchoring the mussel) must be intact!

- The animal must be kept at the dealer under at least adequate, preferably good lighting conditions.

- And very important: only buy captive-bred animals!

If you have acquired a healthy animal, keeping it in an aquarium is quite simple:

The water should be clear and free of sediment. The lighting conditions must be optimal. The location and light intensity are determined by the colouring: Very colourful animals can be placed directly under light, dark and brownish animals must be slowly acclimatised to the HQI light so that the zooxanthellae are not damaged.

The stand should be gently flowed through so that no sediment can be deposited on the mantle lobe.

Socialising with fish is no problem, as long as they are not angelfish. Of course, as with any new acquisition, the full range of possible reactions of the ‘old inhabitants’ must be considered and observed (territorial behaviour, changes in the current in the aquarium…) because unfortunately there are always the odd cleaner or butterfly fish that annoy the mussels.

By the way – giant clams can live up to 100 years in the wild – we probably won’t manage that in the aquarium, but 20 years is not uncommon!

Header image: Tridacna sp. in a marine aquarium. Photo: Andreas Berns