Thanks to chickens, everyone knows what a bird’s egg looks like. But it’s not just chickens that use eggs to produce their offspring. In fact, ‘egg laying’ is the most common method of reproduction in the animal kingdom. Not only insects or arthropods, snails & mussels or other invertebrates reproduce via eggs, but also many vertebrates such as fish — as well as amphibians and reptiles.

In general, eggs consist of the egg white, yolk and the germ spot on the yolk, from which the embryo later develops. In bird’s eggs, the yolk is suspended from two chalazes (hail cords), which keep the yolk in the centre of the egg white. These hail cords are familiar from breakfast eggs. Thanks to this suspension, regular turning does not harm a bird’s egg, in fact it is necessary so that the egg is evenly warmed during incubation. This ‘rearranging’ of the bird parents in the nest is familiar from many nature films.

Do not move!

The situation is different with reptile eggs: there are no chalazae here. The amnion (also known as sheep skin), a protein sac in which the embryo grows, is lighter than the egg white. It therefore rises in the egg and then sticks to the upper wall of the egg. If a reptile egg is then turned later, the amnion is at risk of tearing off and being damaged. This is why the eggs of reptiles must not be turned, but must always remain in the orientation in which they were found.

Another difference to bird eggs lies in the shell: reptile eggs do not have a hard calcareous shell, but are more leathery, with the hardness of the shell increasing as the egg ages.

Where to put the (future) offspring?

If you keep reptiles, you may find yourself in a situation where one or more of your animals wants (or needs) to lay eggs. It is therefore important that you provide species-appropriate egg-laying conditions! The soil substrate you provide is particularly important here. It must have a suitable consistency for the eggs and be generously filled. The temperature and humidity conditions must also fulfil the necessary requirements. It is also important to find out the exact requirements of the reptile species being kept.

Eggs cannot be laid quietly, especially in cramped or overcrowded enclosures. Apart from the fact that keeping pets with too little space or too many animals is not animal-friendly anyway, your pet needs a lot of peace and quiet to lay its eggs. It may therefore be advantageous to temporarily keep it alone to ensure undisturbed egg-laying.

To lay eggs, the mother not only needs different conditions depending on the species. The individual animal also likes to have several options to choose from for laying its eggs. It is therefore your task to fulfil the ‘preferences’ of your mother animal with the options available in your terrarium.

For many lizards, an opaque plastic box with an opening filled with a slightly damp mixture of peat and sand has proved to be a good place to keep them. You can make such a box from an empty ice pack, for example, by cutting out a corner of the lid.

Snakes, on the other hand, like to lay their eggs under flat pieces of bark in the moist substrate or in flower pots lined with moss. Turtles, on the other hand, prefer sand hills.

(Expectant) mothers need better

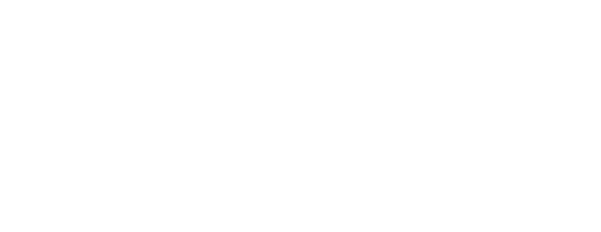

SOLAR RAPTOR® Timer Controller

- Switchable socket strip

- CON-T: Temperature/time control

- CON-TH: Temperature/humidity/time control

- Quick setting desert/tropical mode

incl. VAT

plus shipping

The production and laying of eggs demands a lot from the females. For example, there is a significantly increased need for nutrients, vitamins and minerals in the weeks leading up to egg laying. Egg production increases the demand for calcium, which can lead to calcium deficiency in the mother. This can lead to the animal ultimately lacking the necessary strength to lay eggs. It is therefore essential to ensure that the necessary minerals and vitamins are supplied when you realise that one of your females could be pregnant.

If everything goes smoothly, the ‘mother-to-be’ will carry out a few ‘test digs’ immediately before laying her eggs and stop feeding. The eggs should be laid shortly afterwards.

Highest danger: Laying distress

The main danger around pregnancy is the dreaded laying distress (dystocia). This poses an acute and concrete threat to your pet’s life, so it is important to do everything possible to avoid this danger!

In the event of laying distress, the eggs produced remain in the female’s body and she is unable to bring them out. This can be easily diagnosed using X-rays.

As a result, the animal becomes ill and often dies. If a laying distress is recognised early enough, medical treatment, for example with hormones, can often help. If this does not work, surgical intervention may be necessary.

It is therefore crucial that you recognise a laying distress at an early stage and then present the affected animal to an experienced vet as soon as possible. Laying distress is very painful for the eggbound animals!

The problem of laying distress occurs mainly in turtles and lizards, only rarely in snakes (here most likely in corn snakes). Aquatic turtles are particularly frequently affected by laying distress, as their aquariums unfortunately all too often lack suitable egg-laying sites.

This is already the most important tool you have to prevent laying distress: optimising the laying conditions. However, organic factors can also lead to laying distress – even too low housing temperatures can promote laying distress. Young females laying their first eggs are affected more frequently, for example if the eggs are ‘too big’ for the body passage. You should therefore never mate animals that are too young.

Deformed eggs or eggs that are too soft or too hard can also result in the female not being able to push them out of her body.

Caution: Some reptile keepers are completely unprepared when faced with laying distress. They only keep females and therefore don’t think about the fact that ‘eggs’ could be an issue. However, females kept alone can also lay eggs (albeit unfertilised ones)! If they do not find suitable conditions, they are also at risk of laying distress!

Tips:

As a terrarium owner, you observe your animals on a daily basis. Even if you only keep females, always look out for possible signs of (impending) laying distress!

Optimised laying conditions in terms of substrate, but also the right temperature and humidity, protect and support your females when laying. Timer controllers such as the CON-T/CON-TH help to control the optimum environmental conditions in the terrarium.

But how do you recognise (incipient) laying distress?

Recognising symptoms of impending laying distress

A laying distress usually takes place over several phases. The tricky thing is that a phase with initial signs is often followed by a second phase of apparent recovery. It is easy to be misled by this, which is why it is important to keep a very close eye on (possibly) pregnant females!

Symptoms of the 1st phase:

- Erhöhte Aktivität und auffällige Unruhe (Ihr Tier sucht nach Orten, um seine Eier abzulegen)

- Digging tests at various locations

- Loss of appetite, refusal to eat

- Sometimes pressing movements and/or a tense abdominal wall also occur

Symptoms of the 2nd phase:

- Very frequent return to normal behaviour

- Appetite also returns frequently

- Tortoises sometimes show a weakness of the hindquarters with protective movements of the hind limbs

Symptoms of the 3rd phase:

- Severe impairment of general condition, reluctance to move, lethargy

- Pale skin, sunken eyes, your animal now looks clearly ill

- Refusal to eat, weight loss

- Tense abdominal wall and/or bloated lower abdomen

- Often cramp-like movements and relieving postures

- Foul-smelling discharge (indicates the onset of sepsis)

- Possible regurgitation of food

- Eggs may be laid, but not buried, but scattered randomly around the enclosure. Do not misinterpret this as an ‘all-clear’, as eggs often remain in the oviduct in this case!

Symptoms of the 4th phase:

- Death from septicaemia, general debilitation, dehydration and/or renal failure

Yay, baby alarm!

Once all the hurdles have been successfully overcome and your female has laid all her eggs, you may want to incubate them to ensure successful offspring. But be careful here too!

As already described at the beginning, reptile eggs should not be moved if possible. Under no circumstances should they be turned! So dig out the eggs very carefully. A brush, as used in archaeological excavations, can be very helpful for carefully uncovering the clutch. Once the eggs are exposed, use a pen to carefully mark the top and the cross-section in the exact position in which they were laid. These markings ensure that you do not change the original position of the eggs when transferring them to the incubator and positioning them there.

What can it be? Male or female?

Now it’s time for incubation. You are spoilt for choice here, as the sex of many species is determined by the incubation temperature. With leopard geckos, for example, incubation at around 26 °C produces more female offspring, while temperatures of around 28 °C produce more males. With many turtle species, however, the opposite is true, with more females hatching at higher temperatures. Therefore, choose the incubator temperature carefully according to the specific requirements of your reptile species.

Another thing to bear in mind is that the higher the temperature, the faster the hatchlings will hatch. At the same time, however, the number of malformations also increases at higher temperatures. So patience is also a virtue here…

You can use the time gained to think about and organise where ‘your scaly offspring’ will live later on.

Fun fact: More eggs thanks to corona

Speaking of offspring and egg-laying problems: Like many other wild animals, many reptile species around the world suffer from the problem of dwindling habitat, especially when it comes to egg-laying opportunities. And without egg-laying, no offspring.

However, while the coronavirus has affected humans globally, wild animals worldwide have benefited from the pandemic. This is particularly true for many turtle species, such as the endangered leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea). The females of this species return every two to three years to the beach where they once hatched to lay their eggs.

Researchers in Florida and Thailand have now been able to document significantly more leatherback turtle nests during last year’s nesting season. According to reports, there were more nests in Thailand than at any time in the last 20 years! And even biological stations in the Mediterranean reported similar results. There, the hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) laid more eggs last year.

The reason for this is the reduced noise pollution caused by humans in the coronavirus era. Less shipping traffic, oil and gas extraction, fishing and tourist-free beaches had a very positive effect. After all, the reptiles need one thing above all else to nest – peace and quiet.

Header image: Hatching gecko. Photo: Andy Holmes via Unsplash